- Home

- Julia Keay

Farzana Page 27

Farzana Read online

Page 27

Needless to say this did not meet with her approval. She urged the Governor General to change his mind and then settled for a policy of prevarication. She wrote (or rather she dictated to her munshi Gokul Chand) long letters to Marquess Wellesley listing the value of her assets in Sardhana for which she expected to be recompensed; she made almost outrageous claims about the size, form, value and location of the estates she would accept in exchange; and she insisted that she could not agree to move until she could be sure that accommodation was ready and waiting for her dependents whom, probably without exaggeration, she estimated at ‘near a thousand destitute persons and lame and blind people’.

Months then passed with no estates having been found that matched her demands. She was just beginning to think her tactics might have succeeded when she received another letter from the Governor General saying that he had changed his mind; he now wanted her out, whether or not there was somewhere else for her to go. She would still be given ‘an equivalent portion of territory’, but it ‘might necessarily occupy some time before it can be effected’.21

Interpreting this as proof that Wellesley was trying to cheat her out of her possessions, Farzana changed tactics. By virtue of its location, Sardhana and its brigade had been employed to protect Delhi from the Sikhs for twenty-five years. Now that Delhi had changed hands it would be the British who felt threatened by the desperate Sikh bands who had been ‘the terror and plague of this part of India’22 for more than a generation. Moreover, the Sikhs had finally acquired an effective leader in the young one-eyed Ranjit Singh, the self-proclaimed ‘Maharajah of the Punjab’. Instead of confronting bands of wild and undisciplined factions, the British would soon find their progress blocked by a ‘Sikh Empire’ with the best army in India. Castigating Wellesley for his bad faith, Farzana therefore announced that she was about to open talks with the Sikhs, who would surely be interested in an alliance with anyone who had a grievance against the British.

The very word ‘Sikh’ already made British collars suddenly feel uncomfortably tight. Although Farzana’s threat had no discernible effect on Marquess Wellesley in faraway Calcutta, it made British officials in Delhi sit up and take notice. In December 1804 Archibald Seton, senior East India Company civil servant in Delhi, suggested to the Governor General that ‘conciliating her might in the present state of affairs be a simple and effectual means of restoring and preserving the tranquillity of the upper part of the Doab’.23David Ochterlony agreed. Recently confirmed as Resident and by now as well acquainted with the political situation in ‘the upper part of the Doab’ as he was with Farzana, he warned Wellesley that ‘her influence in this quarter is greater than can be well imagined’ and that it would be extremely dangerous to let her ally herself with the Sikhs. In Ochterlony’s opinion, all that was needed to bring her round was British confirmation of her jagir.

She is afraid of the loss of her districts and of the disbandment of her troops and such is her desire of power that I am perfectly convinced she would encounter any odds to retain both in their present state. I believe that assurances of their integrity during her life would immediately induce her to declare in our favour, but at present she considers all assistance to us as accelerating her own downfall.24

There could be only two reasons why Marquess Wellesley so determinedly ignored all this well-informed advice; either he relished the prospect of taking on the Sikhs or he was not prepared to be outmanoeuvred by a woman. Perhaps it was a combination of both. For eighteen months he had refused to countermand his orders for her to leave Sardhana, and for eighteen months Farzana had dug in her heels. But she had no other weapons in her arsenal and would surely have had to admit defeat had the Governor General not been recalled to England in July 1805. Wellesley’s endless wars had landed the East India Company with unacceptably heavy debts. The directors had decided to replace him with the more conciliatory Lord Cornwallis who had reluctantly agreed to serve a second term as Governor General.

Within a month of Cornwallis’s return his attention was drawn by the now Lord Lake to the ‘problem of the Doab’. The new policy of preserving peace in the country, said Lake, made it ‘particularly necessary to conciliate the Begum Sumru, and to inspire her with a just confidence in the favour and protection of the British Government’.25 Cornwallis, who knew of Farzana from his previous term in office and who was appalled by the idea of a confrontation with the Sikhs, took little convincing. On 16 August 1805 a letter was delivered to Sardhana palace from the new Governor General.

‘I have resolved,’ it read, ‘to leave you in the unmolested possession of your jagir, with all the rights and privileges which you have hitherto enjoyed.’26

It was a remarkable victory. Through sheer perseverance and bloody-mindedness Farzana had emerged from her lengthy tussle with all she could possibly have wanted. The jagir of Sardhana was hers for ‘as long as she may live’ and her position was guaranteed by a power that now had no serious rivals within Hindustan.

14

BEST-LAID PLANS

At the back of the Governor General’s mind as he conceded to Farzana’s demands must have been the hope that the princess would now retire quietly to her estates and leave him in peace. She had her jagir, she had ‘all the rights and privileges which she had hitherto enjoyed’ and nominally at least she was still commander-in-chief of the Sardhana Brigade. What more could she possibly ask?

It was not an unreasonable question, and for nearly a year the answer appeared to be ‘very little’. As part of her deal with Cornwallis the Sardhana Brigade had, like Skinner’s Horse and other such units, become an irregular component of the East India Company’s forces, a move that had prompted the immediate departure of most of her French officers. Many of her British officers had moved on too, seduced by the amnesty offered to British subjects serving with the Marathas, plus the promise of more lucrative commissions in the Company’s army.

Since anyone ‘not descended from European parents on both sides’ had been disqualified, as of 1795, from serving in the Company’s regular army ‘except as pipers, drummers, bandsmen and farriers’1 a high percentage of the Sardhana Brigade’s officer corps would now be Anglo-Indian or Indo-European. Captain Saleur had stepped down as military commander after the battle of Assaye and, at nearly eighty, was enjoying a comfortable and well-earned retirement as one of Farzana’s many pensioners. Its new commander, the son of a Flemish father and an Indian mother named Claud Pathod, had been ordered to hold the brigade where it was and continue to guard the northern frontier of what was now British territory. For the first time in forty years Farzana had no need to worry about its loyalty or its deployment. Instead she could concentrate on keeping her estates profitable, her hundreds of dependents fed and accommodated and her expanding household under control.

One of her less palatable duties during the year (1805–06) was to sponsor the marriage of Louis Balthazar’s seventeen-year-old daughter Julia Anne to George Alexander Dyce. Although he claimed to be related to her friend Colonel David Ochterlony (who did not deny the connection*), Farzana recognized Dyce as a grasping opportunist who had his eyes on her fortune, which he expected would one day pass to Julia Anne. But as the union had the blessing of the girl’s mother (Juliana), Farzana accepted it and, perhaps with hopes of reforming Dyce, offered him a commission in her brigade and gave the couple a home in Sardhana. The marriage lent renewed urgency to a matter that had been exercising Farzana’s mind for some time but that she had thus far failed to address. She had no heir. And until and unless she nominated one, it was entirely possible that an unscrupulous fortune-hunter like Dyce would end up in control of everything she had worked for. The marriage also presented her with the possibility of a solution, but her schemings were interrupted by the announcement, in November 1806, of the death of Emperor Shah Alam.

With its new British masters now firmly in control, Delhi was enjoying a period of peace and confidence unknown since the days of Mirza Najaf Khan. When Farzana retur

ned to the city to mourn the passing of her sovereign and pay her respects to his successor, she found it greatly changed. To her dismay, and to his own bitter disappointment, the British Resident, Colonel David Ochterlony, had fallen victim to his government’s policy of demilitarization and had been replaced by Archibald Seton, a career civil servant. Likewise, when Lord Cornwallis, who held the military rank of Lieutenant General, had died only two months into his second term as Governor General, he had been replaced by Sir George Barlow, an expert in revenue administration. British civilians were moving to Delhi in increasing numbers, and ‘having once come they generally stayed.’

‘Long residences became common,’ writes Percival Spear, ‘private mansions were built and the British settled in as they did nowhere else up-country.… Their mansions became landmarks and their families formed a new official aristocracy.’2

Although she had yet to meet a European woman, European men had been Farzana’s closest companions since she was little more than a child. Completely at home in their company, and as attracted to aristocracy of any description as ever, she moved eagerly into the orbit of the new ruling elite. The just-installed Emperor Akbar Shah II had expressed his imperial gratitude for her long and devoted service to his father by presenting her with a section of the beautiful Khas Bagh (Private Garden) created in 1650 by Jahanara, daughter of Emperor Shah Jahan, just outside the walls of the Red Fort. Here, amid the pools and fountains and formally planted parterres, Farzana proceeded to build herself a city palace stately enough for a sovereign princess and neoclassical enough to commend itself to the new British rulers of the city (and now large enough to house north India’s biggest electrical goods wholesale market).*

When the palace was completed in 1808, Farzana celebrated with a lavish reception. The guest of honour was the superlative monarch, the Padishah, the Mughal Emperor Akbar Shah II, recently demoted by the British to mere ‘King of Delhi’; and the chronicler of the evening was the inimitable Gokul Chand, whose verses would once again challenge his translator.

From the entrance through the garden laid

A carpet that from silk and gold was made.

So many precious items were assembled

They cargo from a hundred ships resembled.

Khilauts, jewels, silver, gold and more

Each guest provided from this generous store.

The food and drink purveyed for delectation

Were prodigal, defying all description.

Dancing thrilled and music sounded

Songs, like nightingales, resounded.

The Padishah filled with pleasure and delight

Gave many thanks for that most wondrous night.3

Because no respectable Hindu or Muslim woman ever appeared in mixed company, Farzana was a novelty. Her British guests had never met anybody quite like Her Highness the Christian Princess of Sardhana and, as intended, they came away dazzled. Praising their tiny hostess as ‘lively, intelligent and very amusing’,4 they thought her hospitality ‘magnificent’, her palace ‘handsome and spacious’, the rooms ‘large and well-proportioned’ and their appointments fabulously expensive. Even the stiff-necked few who regarded the building and its contents as displaying ‘a mixture of grandeur and bad taste’ were seduced by her generous hospitality. Subsequent invitations would be keenly sought, and initial doubts would be dispelled when the begum secured the approval of those most fastidious about the company they kept – namely the missionaries and the memsahibs.

MATERFAMILIAS

The secret of Farzana’s success lay perhaps in her extraordinary ability to reinvent herself. Her life spanned almost exactly the chaotic years between the collapse of the Mughal Empire and the advent of the British Empire, ‘a period of surrounding storm and tempest’ which, according to James Baillie Fraser, ‘shook several great powers from their thrones’.5 Yet from the most inauspicious of beginnings, Farzana had picked her way carefully through the chaos, managing not just to survive but to prosper.

An orphaned child sold into slavery by her own mother, she had transformed herself from teenage concubine into competent administrator of her master’s estates and from leader of her own army, ‘as hard as the rocks she rode over and as fiery-eyed and tireless as the horses of her ancestral deserts,’6 into a subtle strategist at the Mughal court. Onwards and upwards she had climbed until she had triumphantly emerged as the ‘Beloved Daughter’ of the Mughal emperor and what one writer calls ‘an indigenous ruler exemplifying the tastes and manners of the higher echelons of north Indian Muslim society’.7

According to James Skinner, this sensational transformation mystified many and led ‘the people in the Dekhan who knew the Begum by reputation to believe her to be a witch’. Certainly there had always been something bewitching about her. But, contrary to much subsequent conjecture, there was more to her than just irresistibly good looks and a healthy appetite for male company.

‘From the time she put herself under the protection of the British Government,’ wrote William Sleeman, ‘she by degrees adopted the European modes of social intercourse.’8 This did not mean merely giving and attending parties. It meant identifying and then disarming anyone who looked likely to obstruct her access to the higher echelons of British society. A final reinvention of herself was under way.

In the autumn of 1810 the Reverend John Chamberlain was summoned to her Delhi palace for a job interview. Greeted by ‘exceedingly attentive’ servants, the young clergyman was escorted up the stairs and into the main reception hall to meet the begum. ‘Her Highness sat on a musnud,’ wrote Chamberlain in his diary, ‘her shrivelled person almost lost in Cashmere shawls and immense cushions.’ Beside her, on a separate pile of cushions, sat a small boy ‘in a full court suit, with waistcoat and shorts of crimson satin, a sword dangling at his side and a cocked hat’.9 This, indicated the begum, was her son David, and should the Reverend prove a suitable tutor, David was to be his pupil. Masking his surprise at the disparity in age between the begum, who was in her sixties, and her son, who was barely two years old, Chamberlain noted that he was a lively child and a ‘great pet’ of the begum, ‘for which cause I doubt I will be able to do as I would with him’.

The first child born in Sardhana to George Alexander Dyce and Julia Anne had been a girl, but when a boy was born eighteen months later, Farzana had moved quickly to claim him. Citing the centuries-old tradition that had allowed, for example, the heirless Mahadji Scindia to adopt Daulat Rao, she had ignored George Alexander Dyce’s howl of indignation, brushed aside Julia Anne’s feeble murmurs of protest and whisked the six-week-old infant back with her to Delhi as her son and heir. Baptized David Ochterlony Dyce in honour of the former British Resident, the boy was Walter Reinhardt’s great-grandson.

Determined that her heir should also ‘adopt the European modes of social intercourse’, Farzana had decided that David Ochterlony Dyce must grow up speaking perfect English. Her own command of the language was shaky – some visitors insisted that she spoke no English at all, others that she understood it well enough and could sometimes be persuaded to venture a few words. In the matter of a tutor for the boy her preference, Chamberlain noted, would have been to engage a Catholic. ‘The Begum behaves very well to me,’ he wrote, ‘though I have reason to conclude that she does not altogether like my [Anglican] religion.’10 She did already have a Catholic priest on her payroll back in Sardhana, but since the whimsically named (and, when Farzana’s back was turned, outrageously behaved) Father Julius Caesar Scotti was Italian, and since as far as she was concerned an English tutor had to be an Englishman, Farzana was forced to settle for the Protestant Chamberlain.

The arrangement worked well for both princess and tutor – ‘I breakfast with her every morning, Sundays excepted, and hand her to and from table,’ wrote Chamberlain. But it came to an abrupt end when Chamberlain was caught actively proselytizing at a Hindu festival. Farzana raised no objection but the British authorities still looked on such overt missionary activi

ty as provocative of Indian unrest and insisted on his dismissal.

David Ochterlony Dyce proved a sweet-natured child, though he was neither a willing nor an able pupil. Blaming this on Chamberlain’s inexperience as a teacher rather than on the child’s natural indolence or her own over-indulgence, Farzana sent the boy back to Sardhana to continue his education under Reverend Henry Fisher, the East India Company chaplain at Meerut. Although Fisher was a member of the Church Missionary Society, he was a less aggressive evangelist than Chamberlain, and had already been entrusted with the education of the other children in Farzana’s care, including George Thomas’s sons George, John and Jacob and Robert Skinner’s son (also Robert).* Chamberlain, undeterred by his dismissal, took himself off to Calcutta to try his skills on the heathens of Bengal. Fisher would remain in Meerut for nearly thirty years and would tutor more than one generation of Anglo-Indian Thomases, Skinners and Dyces at Farzana’s expense.

Just as she was spared the zeal of the missionaries by being already a Christian, so she deflected the snobbery of the memsahibs by being a princess. Until Chamberlain described her sitting on her musnud surrounded by shawls and cushions, the most recent pen portrait of Farzana had been George Thomas’s wistful memoir of her ‘fair complexion, her black, large, animated eyes and her perfect Hindustani clothes’. But as soon as the newly arrived memsahibs had unpacked their writing cases and sharpened their nibs, every aspect of her appearance, wardrobe and conduct would be described in meticulous detail. She welcomed this scrutiny. ‘[Begum Sumru] is particularly affable to European ladies,’ noted Lieutenant Thomas Bacon, ‘and seldom permits them to quit her presence without bestowing on them some token of her generosity, either a cashmere shawl or a piece of silk or a jewel to the value of 20 or 30 guineas.’11

Anne Deane, the wife of a colonel in the East India Company army, was introduced to Farzana at ‘an elegant breakfast’ given in her husband’s honour by British Resident Archibald Seton in the spring of 1809. Purring with pleasure at meeting ‘a princess in her own right with rank next after the royal family’,12 and not a little in awe of a woman who ‘has been frequently known to command her army in person on the field of battle’, Mrs Deane studied the begum closely. ‘Her features are still handsome,’ she noted, ‘although she is now advanced in years. She is a small woman, delicately formed, with beautiful hazel eyes, a nose somewhat inclined to the aquiline, a complexion very little darker than an Italian, with the finest turned hand and arm I ever saw. She is universally attentive and polite, and a graceful dignity accompanies her most trivial actions.’13

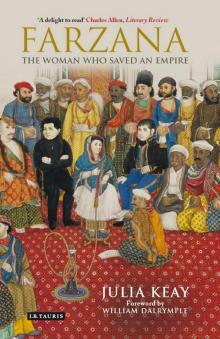

Farzana

Farzana