- Home

- Julia Keay

Farzana

Farzana Read online

JULIA KEAY was the author of several acclaimed biographies including The Spy Who Never Was, With Passport and Parasol and Alexander the Corrector. She also wrote numerous BBC radio documentaries, including two plays, and, with her husband John Keay, co-edited two editions of the Encyclopaedia of Scotland and the third edition of The London Encyclopaedia. The text of Farzana was completed just before her death in 2011.

‘This book, about an amazing woman, now stands as a fitting

memorial to another. Julia will be greatly missed, and this book

shows what an enjoyable writer we have lost.’

William Dalrymple

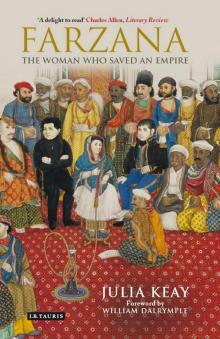

‘A delight to read.’

Charles Allen, Literary Review

New hardback edition published in 2014 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

First published in India in 2013 by HarperCollins Publishers India

Copyright © 2014 the Estate of Julia Keay

Copyright Foreword © 2013 William Dalrymple

The right of Julia Keay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the Estate of Julia Keay in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 055 6

eISBN: 978 0 85773 569 0

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

CONTENTS

Foreword

Prologue

PART ONE: MARRIED TO THE REGIMENT

1750–1778

1 Where Passions Rage

2 In Between Empires

3 The Butcher of Patna

4 Enchanted by Her Heroism

5 A Home of Their Own

PART TWO: DAUGHTER OF THE EMPEROR

1778–1788

6 Steel Beneath the Muslin

7 Fit for Service

8 Fearless Foreigner

9 Violence, Rapine and Barbarity

10 Errors of Judgement

11 A Gathering Storm

12 A Salutory Experience

PART THREE: THE ONLY LADY AT THE TABLE

1788–1836

13 A Genius for Majesty

14 Best-laid Plans

Epilogue

Afterword

Notes

Select Bibliography

FOREWORD

In the first fifty years of the eighteenth century, Delhi and its region was transformed from one of the richest and grandest capitals of the world to an insecure battle zone, disputed by rival warlords, depopulated by half a century of massacres, and looted by a succession of brutal marauders. It was, however, still full of reminders of the magnificence of its past.1

The approach to the city set the tone. For miles in every direction, half collapsed and overgrown, robbed and re-occupied, tottering and disintegrating, neglected by all, lay the remains of six hundred years of Indian imperium. Hamams and palaces, thousand pillared halls and mighty tomb towers, empty mosques and semi-deserted Sufi shrines: there seemed to be no end to the litter of ages, the vanity projects of a hundred forgotten sultans, the products of the piety of a thousand long-dead Sheikhs. ‘The prospect towards Delhi, as far as the eye can reach is covered with the crumbling remains of gardens, pavilions, mosques and burying places,’ wrote Lieutenant William Franklin in 1795. ‘The environs of this once magnificent and celebrated city appear now nothing more than a shapeless heap of ruins…’2

It was a similar scene inside the city walls. The mansions of the nobles were larger than the city palaces of any European nobles, but they lay in a state of terminal disrepair and untended, were collapsing on every side. In the palace itself, the greatest treasures of the Red Fort had all been removed by Nadir Shah in 1739; fifty years later, in the summer of 1788, the marauder Ghulam Qadir personally blinded the Emperor, and then threw vinegar in the wounds by carting off his fabulous library (most of which he then sold to the Nawab of Avadh, much to the Emperor’s fury3). The costumes of the court were threadbare and the precious stones had been picked out of the pietra dura work of the Imperial apartments. A blind emperor ruled from a ruined palace; most of the talented poets and artists had fled to Lucknow (with the single important exception of the mystic poet Mir Dard). Only those too old or decrepit or impoverished to leave remained.

Nor was it just the travellers who looked with sadness at this vast crumbling necropolis. Delhi-wallahs, particularly those who remembered better days, wept at the fate of their ransacked city: ‘How can I describe the desolation of Delhi,’ asked the poet Sauda. ‘There is no house from which the jackal’s cry cannot be heard. The mosques at evening are unlit and deserted. In the once beautiful gardens, the grass grows waist-high around fallen pillars and ruined arches.’

It was in this Delhi, and on its Doab outskirts, that the Begum Sumru of Sardhana presided over one of the most fascinatingly hybrid courts in India. The Begum was originally said to have been a part-Kashmiri dancing girl whose rapid rise to fortune began when she became the bibi of a German soldier of fortune in Mughal service, Walter Reinahrdt known as ‘Sombre’ (Indianized to ‘Sumru’) after his severe expression.

When the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam gave Reinhardt a large jagir [or estate] north of Delhi, Reinhardt’s Begum went with him and turned the village of Sardhana into their capital, with a ruling class drawn both from Mughal noblemen and a ragged bunch of over 200 ne’er-do-well French and Central European mercenaries, many of whom converted to Islam and took Muslim names4. After Sombre’s death, his begum ruled in his stead, partly from Sardhana, and partly from her large palace on Chandni Chowk. She converted to Catholicism – while continuing to cover her head in the Muslim manner – and appealed direct to the Pope to send a chaplain for her court. By the time the intriguingly named Father Julius Caesar turned up in Sardhana, her plans to build the largest church in northern India were already well advanced.

The culture of the Begum’s circle mixed European and Mughal custom to an extraordinary extent: so much so that at least three of the Begum’s European mercenary officers became poets in Urdu – one, whose pen name was Farasu, turned out to be the son of a German Jewish soldier of fortune Gotlieb Koine by a Mughal princess; he was included in the list of prominent Urdu poets produced by the former principal of Delhi College, Alois Sprenger, while according to another contemporary critic this unlikely poet left behind him a ‘camel load of poetic works’5. Another was ‘Jan’, a son of George Thomas by one of the Begum’s slave girls, who is depicted in the miniatures of the period wearing the extravagant kincob dress, bare feet and raffish haircut of a late Mughal banka or gallant.6

The three-day-long Christmas festivities at Sardhana would be opened by High Mass, ‘and during the following two days … a nautch and a display of fireworks’ during which the Sardhana poets had an opportunity for reciting their verses7. Dussehera, Diwali and Holi were celebrated with equal enthusiasm; in addition to which the Begum also dabbled in witchcraft. Indeed the diary of her heir, the wonderfully-named David Dyce Ochterlony Sombre, contains several references to the Begum employing women to cast spells and conduct exorcisms.8

The way that the Christian converts at Sardhana continued doggedly to keep to their old Mughal customs was not to everyone’s taste: as Fr Angelo de Caravaggio, the Capuchin who followed Julius Ceasar put it: ‘My four years at Sardhana saw the construction of a church and a house. Since I was unable to bring about the abandonment of Muslim customs, and seeing no chance of improvement, I took the decision to devote myself to the education of children… seeing that despite my efforts, Christianity did not affect the customs of the Muslims, I [eventually] returned to Agra with the children.’9.

This fusion of civilisations could sometimes be confusing. The Begum was not alone in crossing cultures at this period. Her fellow Mughal jagirdar, the American-born William Linnaeus Gardner, had married a Shi’a Begum of Cambay, while his son James had married Mukhtar Begum, a first cousin of the Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar. Together they fathered an Anglo-Mughal dynasty, half of whose members were Muslim and half Christian; indeed some of them, such as James Jahangir Shikoh Gardner, seem to have been both at the same time.10* In 1820, Gardner’s Begum came to Delhi to negotiate a marriage alliance between her dynasty and that of the Begum Sumru, using the British Resident in Delhi, Sir David Ochterlony as intermediary: ‘I believe James [Gardner’s eldest son] is to be contracted at the next Ede,’ wrote William Gardner to a cousin,

but can say nothing certain as I am not in the secret. Eunuchs and old women are going between daily [between the two households]… The only thing I have interfered in was to place my veto on the whole Royal Family coming to the shadee [marriage] as I cannot afford it…11

Finally, just as everything seemed to be arranged, there was a death in the entourage of the Begum Sumru who did not hesitate to declare forty days mourning, in the Muslim manner: ‘the Old Begum has thought proper to make a very expensive and tedious mourning,’ reported an increasingly irritated Gardner, ‘and has been feeding all Delhi besides beating herself Black and Blue, and expects Sir David as hakim … to take off her sogh [mourning clothes] at the end of the 40 days.’ Ochterlony duly offered his assistance at the mourning rituals, but confided to one friend ‘that the old Begum so mixes Christian customs with the Hindoostanee that though anxious to do that which would please the old lady, he simply did not know what was required.’12

The strangeness of this hybrid world is reflected still in the architecture which survives today at the Begum’s capital of Sardhana. The vast basilica built by the Begum after her conversion promiscuously mixes baroque and Mughal motifs with a great classical dome rising from Mughal squinches decorated with Persian murqana motifs. Stranger still is the graveyard where the Begum’s European mercenaries are buried in miniature Palladian Taj Mahal’s covered with a crazy riot of hybrid ornament, where baroque putti cavort around Persian inscriptions and where latticed jali screens rise to round classical arches. At the four corners at the base of the drum, where you would expect to find minarets or at least small minars, there stand instead four baroque amphorae.

This world came to an unhappy end. The fabulous fluidity of culture and practices, and the plurality of beliefs which was possible in late Mughal India were completely impossible in the hierarchy-obsessed world of early Victorian London, with its firm social certainties and increasingly rigid racial and religious boundaries. After the Begum died, her state was annexed by the East India Company and her heir, David Dyce Ochterlony Sombre went off to Europe in search of justice.

Stateless, multicultural, multi-lingual and ethnically mixed, he found it hard to fit in anywhere outside the strange kingdom where he was raised. Dyce Sombre was a compendium of contradictions: he was raised by a former Muslim courtesan but became a pious Roman Catholic, and ended his days as both a Knight Templar and a Knight of the Pontifical Order of Christ. Exiled to London, he was blackballed from Gentlemen’s Clubs and reviled in the streets as ‘a Black Bugger,’ but succeeded in marrying a prominent Viscount’s daughter, and became the first Asian, and only the second non-white, to be elected to the Mother of Parliaments. Yet just as it seemed he had succeeded in breaking through the ceiling of high Victorian racial prejudice, Sombre’s election was annulled for corruption, his marriage fell apart and his wife’s family had him declared insane and took control of his fortune. Sombre ended up being incarcerated in a Liverpool lunatic asylum.

Many of the ideas for which Sombre was locked up – his insistence on trying to keep his aristocratic English wife in virtual purdah; his belief in djinns and spirits along with his strong conviction that good and evil spirits were battling over his soul; and his tendency to demand the right to duel the huge the number of people who he suspected of sleeping with his wife – these included the Duke of Wellington, Lord Cardigan (of the Charge of the Light Brigade fame) and his father-in-law as well as various ‘waiters, servants, doctors and tradesmen’ – would have appeared relatively unremarkable in India, and at least some of what people took to be his madness came from cultural misunderstanding rather than insanity.

Then at around 4 a.m. on the early morning of 21 September 1843, Sombre gave his keepers the slip, and disappeared into the night. Undetected, he managed to catch an early morning express train from Liverpool’s Lime Street to London. There he had jumped onto another Express to Southampton, where he made his way on an overnight steam-packet to Le Havre. Within forty-four hours of his escape from Liverpool the escapee reached Paris, and checked into one of the best hotels in town. Shortly afterwards he began collecting doctor’s certificates to show that he was of completely sound mind. With these certificates secured, he began legal proceedings to recover the vast fortune which had been sequestered from him when he was declared non compos mentis, or, in the popular parlance of the time, a ‘nincompoop’

He never succeeded in regaining most of it, despite alleging from his exile in Paris that his unfaithful wife had bribed the doctors to have him locked up so that she could seize his money; he also published a 591 page book, Mr Dyce Sombre’s Refutation of the Charge of Lunacy which he circulated to anyone he thought could help.

He continued to litigate unsuccessfully for a further eight years in an attempt to get his fortune back, though his case was not helped by his increasingly eccentric and publicly immoral behaviour with a succession of prostitutes and a charge of exposing himself in public. He eventually died, dejected and alone, in a cheap hotel in London, having returned to the scene of his humiliations to try one last time to restore his lost reputation. It was only long after his death that his lawyers won a succession of cases proving that he been unjustly treated, and so restored to his executors much of his purloined fortune.13

The sad but strangely attractive world of Sardhana has been told several times, but perhaps never so well as by Julia Keay, who brought her customary style and wit to this amazing story. Sadly it has proved her last book. Soon after she and her husband John came to lunch at my Delhi farm on the last leg of their research for the book, Julia contracted cancer, and wrote it up while battling the disease. She died soon after finishing the first draft. The lively tone of her voice survives in its jauntily attractive and engaging style, and this book, about an amazing woman, now stands as fitting memorial to another. Julia will be greatly missed, and this book shows what an enjoyable writer we have lost.

New Delhi

William Dalrymple

19 September 2013

____________________________

* Both the Gardners and the Skinners began to give both Mughal and European names to their children – thus Susan Gardner was known in the zanana as Shubbeah Begum. The Muslim branch of the Skinner family maintain the practice to this day and Frank Skinner, who controls the bicycle rickshaw rental trade in Meerut, has on the reverse of his business card his Mughal name, Sultan Mirza, written in Urdu script.

PROLOGUE

In the golden age of letter writing, before steam power had shrunk the miles and the telegraph had stolen the news, no mail was more eagerly awaited than that penned by husbands, brothers, sons, fathers

and sweethearts who had gone out to India to make their fortunes. Once delivered – and that could be a year after they were written – such letters were savoured like no others. Scanned in silence, read out loud, reread at leisure and studied minutely, they would then be tied with ribbon and tucked in some place of privilege – the smallest drawer in an escritoire, perhaps, or a scented pocketbook – until such time, please God, as the next one arrived or, better still, the writer himself returned.

Whether short and stilted or long and eloquent, their news was as exciting as their familiar handwriting. Spiced with tales of moustachioed maharajas riding jewel-encrusted elephants and of naked men with long matted hair, they told of tiger-infested jungles, temples dedicated to outlandish heathen gods, debilitating heat and life-threatening illness, fortunes made and fortunes lost. Feats of heroism on the battlefield vied with accounts of the rankest intrigue at the numerous Indian courts; and among these, the scarcely credible exploits of a fraternity of freelance European adventurers excited particular wonder and accentuated the impression of an exotic land where fact was stranger than fantasy.

In these letters of the early nineteenth century, and in journals and memoirs written for posterity as much as family, one name crops up with intriguing frequency – that of a mysterious and apparently warlike ‘Begum’, or princess. ‘Begum Sumru joined us with four battalions…’, ‘Begum Sumru was with her forces operating against a fresh rising of the Sikhs’, ‘Begum Sumru arrived in her palanquin, supported by a hundred men and a six-pounder gun’, ‘…we dined at Begum Sumru’s palace…’, ‘I breakfasted and dined with the old witch…’. A begum is the female equivalent of a nawab, a Muslim prince, but this lady’s enjoyment of the rank also owed something to several wordier titles conferred on her by the Mughal emperor. Of these Farzand-i-Azizi meaning ‘Beloved Daughter [of the state]’ was the most prized. At the imperial court she would be called by this honorific and, shortened and personalized as ‘Farzana’, it is thus that popular history has come to remember her. A heroine needs a proper name. Unlike ‘Begum Sumru’, ‘Farzana’ conveys the requisite intimacy while still implying the status she so jealously guarded.

Farzana

Farzana