- Home

- Julia Keay

Farzana Page 15

Farzana Read online

Page 15

The only contemporary biography of George Thomas, as of Shah Alam, comes from the laboured pen of William Francklin (‘surely one of the dullest and most pompous biographers ever to have netted such a subject’)20. Francklin has little to say about Thomas’s early career beyond that he had reached India some six years earlier as a ‘common sailor’ on a British ‘ship of war’. Herbert Compton, whose A Particular Account of the European Military Adventurers of Hindustan would not be published till 1892, gives Thomas’s date of birth as 1756 and his birthplace as County Tipperary. Keene narrows this down to a farm cottage in the village of Roscrea and claims that he was descended from a Cromwellian Ironside who had settled in Tipperaray in the seventeenth century. This would make the Thomas family Protestants. It might also explain George’s frequent declarations of loyalty to the British Crown (‘I have nothing in view but the welfare of my King, and my country’) and his intense dislike of the French.

Nursing much the same ambitions as had Reinhardt, Madec, and de Boigne, Thomas had jumped ship in Madras and then made his way inland in search of what Francklin calls ‘a life more suitable to his ardent disposition’. He fought with or against the ‘exceedingly lawless’ Poligar chiefs of the Carnatic before signing up as a mercenary in the employ of the Nizam of Hyderabad. This was a useful apprenticeship, but the Nizam’s army was too full of Frenchmen for Thomas’s liking. Moreover, the most ‘ardent’ action was to be found, and the real fortunes were to be made, not in the jungles of Hyderabad but in the plains of Hindustan. So, alone and travelling at least some of the way on foot, he had set out to cover the thousand miles that separated the Deccan from Delhi.

The dates of this perilous journey remain open to conjecture. Compton gives a clue with the assertion that ‘on reaching the city he offered his services to the only body of regular troops in Hindustan, that belonging to the Begum Sumru’. The Sardhana Brigade could have been so described only after the departure of de Boigne’s brigade with Mahadji Scindia to engage the Rajputs in the middle of 1786; and since Thomas was certainly in Farzana’s employ by April 1787, their first meeting seems likely to have occurred between these dates, presumably when Farzana was in Delhi defending the emperor against Ghulam Qadir. ‘Thomas’s application was entertained,’ continues Compton, ‘and he was appointed to a subordinate command in the Begum’s army.’21

His arrival changed more than just the hierarchy of the Sardhana Brigade. Farzana was by now in her mid-thirties. For ten years she had clung with extraordinary tenacity to Reinhardt’s inheritance, administering the estate with such skill that its revenue had risen from six to nine lakh (600,000 to 900,000) rupees and, most impressive of all, managing to keep her turbulent army under control and gainfully employed despite the loss of Pauli. She had achieved all this on her own, without conspicuous confidantes or dependable friends, and regardless of the fact that she was still treated with deep suspicion by those who thought ‘a woman performing a man’s role was a cultural aberration’.22

But to someone who valued companionship as much as devotion, authority was proving a lonely station. Nothing therefore could have been more welcome than the appearance of the engaging and irrepressible Thomas. She came to rely on what a near-contemporary called ‘his wild energy, great foresight, daring intrepidity and gigantic form and strength’.23 She clearly enjoyed his company, and she revelled in the light-hearted confidences that made the most stubborn of obstacles seem trivial. If alarm bells warned of the danger of letting her guard down, she paid them no heed. By the time the 1788 campaigning season brought from the emperor a new summons to arms, she had promoted George Thomas to the command of one of the brigade’s four battalions.

The 1788 summons was not unexpected. In the late affray with Ghulam Qadir, a notable absentee had been the emperor’s protector, paymaster and deputy Vakil. Mahadji Scindia had failed to respond to the imperial appeal for help because he had been in no position to do so. His expedition into Rajputana had not prospered. Forewarned of his approach, the Rajput princes had assembled their combined forces and ridden forth to confront him on the frontiers of their domains. In late May 1787, just after Farzana’s triumphant intervention in Delhi, the opposing forces met near the town of Lalsot, some 45 miles east of Jaipur. With the Rajputs’ superior numbers offset by Scindia’s deployment of de Boigne’s highly trained brigade, the two sides looked evenly matched and neither had much appetite for combat. The May temperatures would have been nigh unbearable; just watering the two armies must have been a logistical nightmare.

The impasse had been ended by the general in charge of Mahadji Scindia’s contingent of imperial troops. As strongly opposed to the supremacy of the Marathas as was the treacherous eunuch Mansur Ali, he had accompanied Scindia into Rajputana with the greatest reluctance. Neither he nor his second-in-command, who was also his nephew, had any intention of risking his life in what they considered a Maratha cause. The two men accordingly entered into secret negotiations with the rajah of Jaipur. In time-honoured fashion, the rajah made generous offers of emolument and employment; these were accepted, a treaty was drawn up, and within days of its arrival the entire imperial contingent had gone over to the Rajputs.

Francklin confidently asserts that although this betrayal had reduced Scindia’s force by more than 14,000 men, he ‘hesitated not to give instant battle’. Others report a delay of several days, and insist that the rajah of Jaipur had to challenge the Maratha before he would ‘come out from behind his guns and fight’.24 Only Scindia’s closest companions knew the real reason for the delay. A messenger had just arrived from Ujjain to report the death of Scindia’s only child, a two-year-old daughter. The tragedy left Scindia ‘prostrate with grief and incapable of leaving his tent for three days’.25 But the battle, once it started, was ‘bloody and obstinate’. Upwards of 2,000 men were killed on each side, including the turncoat Mughal general who, bowled from his elephant by a bouncing round shot, had fallen among the foliage intended for the elephant’s supper and there ‘received a splinter in his temple which proved instantly mortal’. His nephew and deputy, Ismael Beg, stepped into the breach.

Ismael, hearing of this event, exclaimed, ‘I am now the leader!’ and immediately addressed the troops, and concluded the action for that day with a brisk cannonade.26

Despite de Boigne’s best efforts, the Marathas stood no chance against the combined Mughal and Rajput forces. Heavily outnumbered, isolated in enemy territory and desperately short of provisions, they were obliged to withdraw. ‘It was common knowledge,’ Jadunath Sarkar would write, ‘that when retreating from that place, Mahadji Scindia turned his face back to the country and swore “If I live, I shall reduce Jaipur and Jodhpur to ashes”.’27 The Rajputs paid no heed. They had resisted the demand for tribute, withheld recognition of Scindia and were delighted to see the back of him.

Ismael Beg was less willing to disengage. Assuming the grandiose mantle of ‘champion of Muslim rule in northern India’, he pursued the retreating Marathas, forcing Scindia to cross the Chambal river and take refuge in his fortress of Gwalior. Adding insult to injury, Ismael Beg then laid siege to the Maratha-held fort of Agra, in which venture he was joined by Ghulam Qadir, still fanatical, still frustrated and still in charge of his late uncle’s army. Scindia’s route back to Delhi was blocked. This prolonged absence of his supposed protector and paymaster had driven Emperor Shah Alam to despair. His financial plight was now critical. His family was starving, and the few troops that remained loyal to him were poised to leave in search of more remunerative employment elsewhere. Recovering a glimmer of the spirit that had briefly surfaced during Ghulam Qadir’s assault on the Red Fort, the chronically indecisive emperor turned again to his most trustworthy ally. Farzana was summoned to the capital; Thomas accompanied her in his new role as battalion commander; and both must have been pleasantly surprised to learn that for once the ‘king of the world’ was himself to take the offensive.

____________________________

* Sometimes ‘Mahadaji’, ‘Madhaji’ or ‘Madhoji’ and sometimes ‘Sindhia’, ‘Scindea’ or ‘Shinde’

8

FEARLESS FOREIGNER

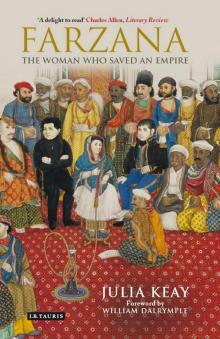

Signs that the arrival of George Thomas had had a profound effect on Farzana were evident the moment they entered the Red Fort in response to the emperor’s call. Rarely for Reinhardt, and never for Pauli, had Farzana gone to such lengths to assert her femininity. Here was no Joan of Arc riding proud and fierce at the head of her troops, no intrepid she-warrior ‘as hard as the rocks she rode over and as fiery-eyed and tireless as the horses of her ancestral deserts’.1 Here, instead, was a vision of demure authority, petite and graceful, draped in silk, reclining among the embroidered cushions of a canopied palanquin borne on the shoulders of a team of turbaned bearers.

This picturesque ensemble was accompanied by three battalions of sepoys, an impressive array of artillery and the pick of her European officers. The unremarkable Baours was still nominally colonel of the brigade, but the choreography left little doubt that the begum’s confidence, and the brigade’s operational inspiration, now lay with the handsome young Irishman who rode by her side.

Thanks to the reminiscences of friends and admirers, George Thomas’s life and adventures in India are moderately well documented. But all such first-hand accounts post-date his arrival in Delhi, so leaving a tempting void to be filled by more fanciful minds. Guesses at the parentage of the ‘bog-trotter from Tipperary’ have ranged from ‘a penniless peasant farmer’ through ‘a well-known horseman who was killed by a fall from his horse’ to ‘the illegitimate offspring of a noble family’. An imaginative cast of supporting characters has also been supplied, including ‘the Tipperary man named Kelly who owned a grog shop in Madras’.2 It was Kelly, so the story goes, who had come to the rescue when Thomas jumped ship in Madras and who advised him to offer his services as a mercenary to the Poligars.

To these ‘exceedingly lawless chiefs’ Thomas had brought some expertise as a naval gunner; and from his subsequent service with the Nizam of Hyderabad, he had acquired a fluency in both Urdu, the military patois, and Persian, the lingua franca of discourse among Muslim rulers in India. In the words of his friend (and sometimes foe) James Skinner, by the time Thomas had reached Delhi at the end of his solitary trek across the Deccan he was so ‘intimately acquainted with the spirit and character of the natives of India’ that of all the European officers known to Skinner ‘none was better qualified to guide and command them’.3

The sepoys of the Sardhana Brigade probably agreed. A fearless foreigner, over 6 feet tall and immensely strong, who spoke their language, relished their food and enjoyed their jokes just as heartily as he kicked their backsides – here was a man whose authority they were willing to tolerate. His military skills were immeasurably greater than their own; his horsemanship was unsurpassed; he was also a crack shot and an expert swordsman. He could drink the most hardened of ‘drunken scoundrels’ under the table and still call for more liquor. So infectious was the bellow of enthusiasm with which he spurred his mount to charge into action that his men would follow him anywhere. Never before had Farzana’s troops been so amenable.

Her officers though were more cautious. Those of mixed race would be defined by Keene as ‘the offspring of connections which British officers in those days often formed with native females’, though they might equally have been of part-Portuguese, French or of other European extraction. Such ‘Indo-Europeans’ generally welcomed the new arrival’s devil-may-care antics and appreciated his refreshing lack of condescension. Many would become his closest friends. Even those of wholly European descent would rarely accuse the Irishman of the arch-crime of ‘giving himself airs’. But all these non-Indian officers resented his easy camaraderie with the sepoys they had so often struggled to control, and they were especially jealous of the close relationship that was developing between the dashing Irish sailor and the lady, half his size, to whom they owed allegiance.

The French officers, in particular, cordially detested him, and Thomas cordially reciprocated the sentiment. He made no secret of his contempt for a country whose citizens were clamouring for an end to the monarchical ancien régime (the French Revolution was already gathering pace); even among the Frenchmen who were his fellow officers he suspected disruptive egalitarian tendencies. He also berated them for monopolizing the senior posts in the Sardhana Brigade, for paying themselves far more than their share of the brigade’s income, and ‘for keeping their mistress in a chronic state of pecuniary difficulty’.4 Thanks in part to Reinhardt’s fortune and in part to her own endeavours, Farzana was not in fact even temporarily short of funds. But she was clearly gratified to have a concerned champion of such reassuring stature and confident sentiments. She did not therefore intervene, and though tensions may have been building within the Sardhana Brigade, she paid them little heed. When the brigade reported for duty at the Red Fort in 1788 – she in silks, Thomas in close attendance – the prospect of action sufficed to banish all thoughts of dissent.

ON THE WARPATH

Still desperate for revenue, the emperor was proposing another approach to the recalcitrant Rajputs. But this time it involved his personal participation. Shah Alam was prepared to gamble that, although the rajah of Jaipur had managed to avoid handing over his arrears of tribute to Mahadji Scindia, he would not be so evasive if confronted by the emperor himself. The emperor had, of course, ordered the Rajput to bring the money to Delhi, though the order was couched as an invitation. But the rajah, as much in fear of a palace coup in his absence as any other Indian ruler, was unwilling to leave Jaipur territory. Instead he had suggested a compromise: if the emperor would deign to meet him halfway, he would hand over as much as he could afford.

In no position to force the issue, Shah Alam had accepted this suggestion and, gathering up the shreds of his imperial dignity, had prepared to impress the Jaipur rajah. His illustrious forebears, the Great Mughal emperors Akbar, Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, had been accustomed to process through their empire attended by ‘vast numbers of elephants, flags of all descriptions, the finest horses magnificently caparisoned, and officers dressed in cloth of gold’.5 Their court and capital moved with them. Two tented cities, each laid out identically, leapfrogged one another across the countryside so that, at the end of each day’s march, the whole travelling concourse found itself in familiar surroundings. Everything, from the imperial chambers to the farriers’ lines and the armourers’ workshops, was located exactly as before. The same courtiers paid court, the same supplicants sought an audience. The business of empire went on uninterrupted. When the Great Mughal processed, his world processed with him.

Shah Alam could only dream of putting on such a dazzling display. But he did his best. The royal elephants were led from their stables to be groomed by their mahouts; tusks were polished, and heads and trunks were decorated with coloured powders; threadbare hangings were patched and cleaned, the ornamental headcloths dusted off and the howdahs repaired and reupholstered. In the guardrooms silver fittings were burnished and leather saddlery buffed. But as the emperor knew well enough, pomp and pageantry were not enough; he also needed an army.

Because of the machinations of the eunuch Mansur Ali, whose treachery had still not been fathomed by his credulous sovereign, imperial troop numbers had been reduced to little more than two thousand. Reinforcements were therefore sought from wherever they could be found, with neither calibre nor creed a bar to service. Hence the inclusion of Himmat Bahadur, one of the least trustworthy of those ‘unscrupulous villains who sold his services indiscriminately to anyone he believed to be on the edge of power’.

Himmat Bahadur was in command (if not in control) of a ragtag army consisting entirely of some two thousand fanatical Hindu gosains. Devotees of the god Shiva, by way of a uniform the gosains wore either vestigial loincloths or nothing at all. They smeared their bodies and faces with ash, wore their hair and beards in tangled dreadlocks, and were habitually stoned out of their mind

s on hashish. Although reputed ‘holy men’, they enjoyed nothing so much as a killing spree; indeed according to the Comte de Modave, they were willing to fight without being paid. Hardly a sight to impress, they yet placed their trust in Shiva, believed themselves invulnerable to bullets and might strike terror into the hearts of impressionable opponents.

It was to supplement this disorderly horde that Shah Alam had summoned Begum Sumru and her Sardhana Brigade. The contrast with the gosains was favourable. Farzana herself might currently be disappointing her more fanciful biographers by looking distinctly unwarlike, but under the eagle eye and blistering tongue of George Thomas her ‘band of drunken ruffians’, if not their officers, were giving a fair impression of a workable army.

The dresses of her officers are the most heterogeneous and varied possible, being worn according to the taste or fancy of each without regard to uniformity of pattern or colour, but the troops are clad in vests of dark yellow cloth with some attention to uniformity of cut and they are all armed and appointed alike. They are not very military in appearance but are said to be good soldiers, both in courage and hardihood.6

With the elderly emperor perched in a howdah atop his finest elephant, the bickering gosains kicking up a fog of dust with their calloused feet, the Sardhana Brigade swaggering along at a distance, and the chatelaine of Sardhana swaying gracefully in her palanquin, this combined force was as bizarre an army as had ever set out from the imperial capital. Followed by the usual straggle of attendants – what Modave had described as ‘a veritable walking city of cooks, carters, peons and servants’ – it travelled slowly, taking nearly three weeks to cover the 70-odd miles of rock-strewn semi-desert that lay between Delhi and the frontier of Jaipur territory.

Farzana

Farzana